Countries

Solidarity campaigns

Kazakhstan: a showcase for shrinking civic space

The Nazarbayev regime is using informal and formal methods to squeeze out NGOs, independent media and trade unions. Western governments should pay attention.

Little noticed by the international community, Kazakhstan has become a model case for the global double trend of rising authoritarianism and shrinking civic space. While state pressure has grown continuously since the mid-1990s, the crackdown on civil society has intensified over the last year amid mounting economic hardship.

Like other post-Soviet regimes, the Kazakh leadership uses a myriad combination of tools to squeeze civil society. Legal and practical forms of repression are compounded by increasing restrictions to independent funding, gradually suffocating independent thinking and activism in Kazakh society. The west should open its eyes to the shrinking space in Kazakhstan and do more to support independent civil society as a counter-weight to the increasing state monopolisation of power.

Increasing state control

The latest bout of repression has unfolded in the wake of arbitrary mass detentions following a series of land protests last spring. The protests started in the western city of Atyrau in April 2016 and quickly spread to several Kazakh cities.

According to estimates by the human rights NGO International Legal Initiative Public Foundation, more than 1,000 people were arrested in the biggest city, Almaty, with hundreds more in the capital Astana and many more across the rest of the country. Citizens were protesting not only the new changes to the Land Code, which would allow the sale of land to foreigners, but deep-rooted social and economic problems – unemployment, lack of housing, lack of quality education and poor access to healthcare and medicines. Underlying all these issues is a growing distrust of state power and fear among the population that Kazakhstan’s independence could be lost to systemic corruption.

The regime’s response, too, has been a symptom of a much longer-term trend in Kazakhstan. Among those arrested over the past 12 months have been activists, trade unionists, independent journalists and representatives of human rights organisations. Most recently, the authorities have targeted Zhanbolat Mamai, editor of Tribuna, one of the last independent newspapers, and leading Kazakh human rights NGOs International Legal Initiative, Liberty and Kadyr-kassiet.

February 2017: Zhanbolat Mamai, editor of Tribuna, has categorically denied the money-laundering charges pressed against him. Source: RFE-RL / social media.

The crackdown against these groups came as no surprise to civil society, which has been gradually squeezed over the past 20 years as the state monopolised the economic, political, media and public space. In fact, the Soviet system has been recreated.

One symptom of consistent state monopolisation in all spheres is the continual absence of a free market economy. Today, 80% of Kazakhstan’s economy is under state control in various forms (state-owned enterprises, quasi-public sector holdings, joint-stock companies, private companies reliant on the public sector for tenders and contracts etc.). At the same time, corruption has become systemic and is threatening the national interests of the country. The crisis that hit the Kazakh economy with the fall in oil prices has intensified protest moods in a society where 28%, or 2.5m people, are either self-employed or lack stable jobs and incomes.

A society consisting of people who are dependent on the state remains vulnerable and unable to control their country or defend their interests. In this general atmosphere of apathy, the opposition does not have broad support among the population

Monopolisation in the public sphere has led to a lack of real political opposition and independent media, a strengthening of the repressive apparatus (police, prosecutors, courts, and national security agencies) and a dramatic shrinking of civic space in Kazakhstan. A society consisting of people who are dependent on the state remains vulnerable and unable to control their country or defend their interests. In this general atmosphere of apathy, the opposition does not have broad support among the population. With legal pressures mounting on traditional NGOs, civil activism is finding new ways in informal and unregistered groups and movements.

However, to eliminate potential opponents from the political, economic, information and public fields, the Kazakh authorities regularly conduct regular exercises of “lawn mowing” among opposition and civil society, as was seen in the aftermath of last year’s protests. Like in other post-Soviet countries, arrests and imprisonments in the wake of major protests temporarily garner headlines and serve as a focal point to highlight internal developments. But the international community should understand that the tools employed to restrict civil society run deeper and are symptomatic of closing civil space throughout the post-Soviet region.

Legal restrictions of the freedom of association and its implications for civic space

State laws regulating the conduct of what would be deemed private activities in democratic societies have crept into a number of sectors, affecting economic, political, religious and labor rights, as well as the information sphere and civic space.

To start with, the barriers for entering the political system are unreasonably high. To register a party in Kazakhstan, it is necessary to collect the signatures of 40,000 would-be members. This is an excessive requirement in a country of only 18m citizens and actively prevents the creation and registration of new political parties. In this sense, the system reflects the tendency to preserve the Soviet system — the hegemony of one party with several smaller controlled parties which are created and admitted to parliament to provide a democratic veneer. To this day, Kazakhstan’s political system does not allow for pluralism and bars independent political groups.

November 2016: Workers at Kazstroiservis in western Kazakhstan strike against poor conditions. Source: Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Kazakhstan.

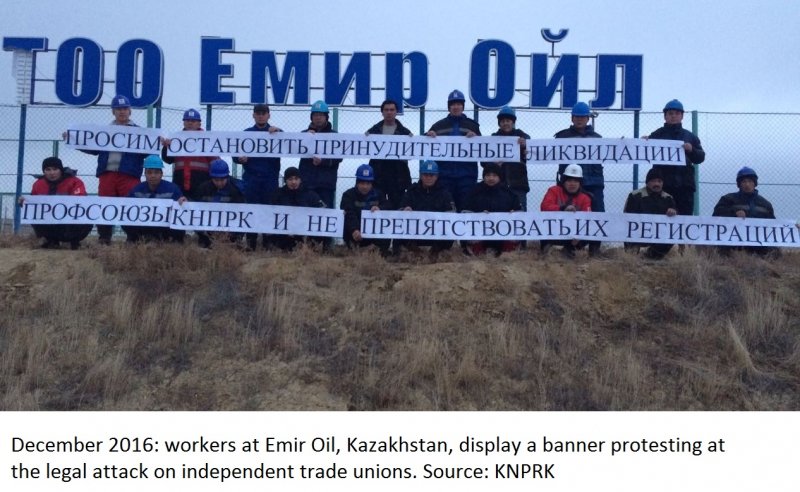

Second, trade unions as an important form of public association are regulated by a separate law, which has recently been toughened against independent unions. The new law recognises only sectoral trade unions and their members or branches, forcing independent trade unions to re-register and effectively enshrining the monopolisation of trade unions by law.

Religious associations are also regulated by special legislation. The religious sphere had already been subjected to full state control when all religious associations were re-registered in 2012-2014, cutting the number of organizations by 25%. In more recent legislation, the state has taken on a double role in allowing and controlling religious activities in the country. Now, it not only determines the number of group members required for registration, but also what religious literature can be used, where and how people are allowed to assemble.

In general, Kazakh legislation reflects a deep distrust of citizens’ activities. Legal requirements for registering public organizations are much stricter than those required by small businesses. Since late 2015, two laws (on non-profit organisations and the law on state social order) have severely restricted the scope of activities of non-government organisations. NGO work is now only allowed in the social sphere, restricting activity in areas such as democracy-promotion or defending human rights.

At the same time, the duties of reporting to the authorities have been excessively expanded, once more underlining the authorities’ distrust of civil society and their attempt to establish total control over the NGO sector. Failure to provide adequate information can lead to warnings, fines or even the suspension of activities for up to three months.

Beyond organisational restrictions, in the criminal sphere, leaders of public associations are treated on a par with leaders of criminal groups under Kazakh laws intended to address terrorism and extremism

Even before this new law, the prosecutor's office could suspend the activities of an NGO for up to six months, and later file a lawsuit in court to liquidate it. Appeals by independent NGOs such as the International Legal Initiative (ILI) proved fruitless. As a result, the oldest Kazakh non-state organisation, the public association Caspiy Tabigaty (Caspian Nature) was closed down after successfully operating since 1992. ILI now intends to file a complaint with the UN Human Rights Committee on the violation of freedom of association.

Beyond organisational restrictions, in the criminal sphere, leaders of public associations are treated on a par with leaders of criminal groups under Kazakh laws intended to address terrorism and extremism. The minimum term of punishment under such law is 10 years imprisonment. Crimes deemed to be “extremist” in nature extends to vague activity such as “the incitement of social discord”. In the absence of a clear definition, the premise of “social discord” allows the judicial system to punish public figures and activists merely for criticising the authorities.

November 2016: Talgat Ayan, pictured here at a land reform protest in Atyrau, was sentenced to five years in prison for his protest. Source: Facebook.

Independent media also experience constant difficulties with registration. According to Fergana News, “the ruling elite regards media activities not as a type of business, but as an instrument of agitation, propaganda and influence on important decisions taken at various levels”.

Editors are responsible for any inaccuracy in the output of a publication and authorities can declare close outlets Independent journalists and publications are routinely persecuted by lawsuits for slander, insult or damaging the business reputation of officials. Independent media are also marginalised by official state financing to state media and loyal publications which creates an increasingly censored and self-censored media landscape completely dependent on the state.

Practical repressions against independent media, civil groups, activists and human rights defenders

In addition to legal obstacles placed in the way of independent groups, Kazakh authorities and state bodies also exert pressure through various practical channels.

For independent media outlets, this can mean being closed down for technical reasons, or being financially ruined trough multimillion tenge fines for damaging the reputation of officials, or through criminal prosecution for libel or insult.

Repression of civil activists is also carried out by intimidation, administrative arrests for participating in peaceful rallies or pickets, and criminal prosecution for inciting “social discord” or organizing illegal rallies. Physical and psychological pressure is regularly used during investigations, especially when activists find themselves in the hands of law enforcement officials.

Over the past year, several activists have been broken down to sign procedural agreements in which they pleaded guilty. Most recently, the public recantationof the activist Olesya Khalabuzar, who had called on Kazakh citizens to change from “slaves into masters”, shocked the political opposition and human rights community.

In exchange, activists have been given suspended sentences and remain under probation, unable to openly express critical opinions. In other cases, the Facebook and Whatsapp profiles of activists were hacked and provocative messages sent from their accounts — messages which were later used to prosecute them.

Restrictions to access to funding, including from abroad

Another effective tool for suppressing and marginalising activities of independent civil society organizations is to restrict their access to financial resources, in particular foreign funding. Over recent years, foreign funding to Kazakh NGOs has been restricted to activities which ostensibly “defend the public interest”.

As a result, international donors have increasingly provided financial support to only those NGOs with good government relations. Under the guise of a so-called “dialogue” between state and NGOs, a new landscape of GONGOs (government-operated NGOs) has emerged. Worryingly, foreign donors have started to support GONGOs, failing to understand that international support for fake civil engagement is toxic for the truly independent civil society.

The legal apparatus has also been engaged to curtail the legislative framework for foreign funding of independent NGOs. The amended law on state social order and grants now limits foreign grants to strictly defined purposes. The scope of NGO activities is restricted to purely social activities, excluding any work on democracy, human or civil rights. In addition, the state has the right to monitor all NGO projects, regardless of where their funding comes from. The law granting this permission was kept deliberately vague, allowing authorities at any time to introduce a grant monopoly for a so-called “operator” (an organisation collecting funds from the budget on behalf of the state).

The west should see Kazakhstan as a showcase for the social degradation that is created by repressive rule across the post-Soviet region and treat it accordingly

Reporting restrictions and burdens have also restricted the space for civil society in Kazakhstan. All non-state, non-commercial organizations (and individuals) have to report to the tax authorities any foreign funding they have received, whatever its purpose. This includes funding for everything from legal assistance to sociological surveys to research.

These reporting regulations fundamentally contradict Kazakhstan’s international obligations. In particular, they undermine the possibility to file individual complaints with the UN Human Rights Committee, as such complaints are often filed with the support of human rights organisations. The new law threatens the confidentiality of information and the right of confidentiality between attorneys and clients.

Conclusion

Until now, international politicians and donors have failed to understand the dangers emanating from the crackdown on civil society in Kazakhstan.

The repression of independent thinking in all social spheres, from politics and economics to culture and media, is leading to an increasing fragmentation of Kazakh society. Moreover, it is generating a mood of apathy and cynicism which — like in the Soviet era — leads to stagnation and undermines the development and modernization of the entire country.

The west should see Kazakhstan as a showcase for the social degradation that is created by repressive rule across the post-Soviet region and treat it accordingly. Instead of supporting fake GONGOs, donors should invest in the development of an independent non-state sector as the best way to build a future with more transparency and civil control of the state.

This article is a condensed version of the research project “Shrinking space for civil society in Kazakhstan” written with the support of the Prague Civil Society Centre.

Source: openDemocracy