Countries

Solidarity campaigns

Kazakhstan is in the top 10 worst countries for workers’ rights

The latest ranking of workers’ rights includes the global top ten, of which no country in 2017 should want to be a part.

The Middle East and North Africa are worst

Once again, the Middle East and North Africa was the worst region for treatment of workers, with the Kafala system in the Gulf still enslaving millions of people:

- The absolute denial of basic workers’ rights remained in place in Saudi Arabia.

- In countries such as Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, conflict and breakdown of the rule of law means workers have no guarantee of labour rights.

- In conflict-torn Yemen, 650,000 public sector workers have not been paid for more than 8 months, while some 4 million private sector jobs have been destroyed, including in the operations of multinationals Total, G4S and DNO, leaving their families destitute.

- The continued occupation of Palestine also means that workers there are denied their rights and the chance to find decent jobs.

Conditions in Africa have deteriorated, with Benin, Nigeria and Zimbabwe being the worst performing countries - including many cases of workers suspended or dismissed for taking legitimate strike action.

The report ranks the ten worst countries for workers’ rights in 2017 as Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, Guatemala, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Qatar, South Korea, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

The Philippines, South Korea and Kazakhstan have joined the ten-worst ranking for the first time this year.

Sombre reading

The 2016 annual ranking makes for sombre reading. Violence and repression of workers are on the increase. In just one year, the number of countries experiencing physical violence has risen by 10 percent. Attacks on trade union members have been documented in fifty-nine countries, fuelling growing anxiety about jobs and wages.

Corporate interests are being put ahead of the interests of working people in the global economy, with 60% of countries excluding whole categories of workers from labour law, undermining fundamental democratic rights.

Denying workers protection under labour laws creates a hidden workforce, where governments and companies refuse to take responsibility, especially for migrant workers, domestic workers and those on short-term contracts.

Key findings

This year’s key findings include:

- 84 countries exclude groups of workers from labour law.

- Over three-quarters of countries deny some or all workers their right to strike.

- Over three-quarters of countries deny some or all workers collective bargaining.

- Out of 139 countries surveyed, 50 deny or constrain free speech and freedom of assembly.

The number of countries in which workers are exposed to physical violence and threats increased by 10 per cent (from 52 to 59) and include Colombia, Egypt, Guatemala, Indonesia and Ukraine.

Unionists were murdered in 11 countries, including Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Italy, Mauritania, Mexico, Peru, The Philippines and Venezuela.

In South Korea, Han Sang-gyun, President of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, has been imprisoned since 2015 for organising public demonstrations during the candlelight revolution, to prevent the now deposed Park government from passing anti-worker labour laws.

Trade union leaders in Kazakhstan were arrested merely because they called for strike action. In the Philippines, the climate of violence and impunity, which has proliferated under President Duterte, had a profound impact on workers’ rights.

Working conditions also worsened in other countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Myanmar.

Argentina has seen a spike in violence and repression by the state and private security forces – in one case, 80 workers were injured during a stoppage for better pay and conditions.The build-up of the 2016 Olympic games in Brazil saw a significant increase in labour exploitation, and the dismantling of labour legislation by the new Brazilian government last year caused a sharp decline of labour standards.

In Ecuador, union leaders were forbidden from speaking out and their offices were ransacked and occupied by the government.

Problems in the garment sector in Myanmar persist, with long working hours, low pay and poor working conditions being exacerbated by serious flaws in the labour legislation that make it extremely difficult for unions to register.

Company action

Companies operating in countries where governments laws and business practices have deteriorated must be aware of the risk to their business and workers. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provides the international benchmark for how companies should operate.

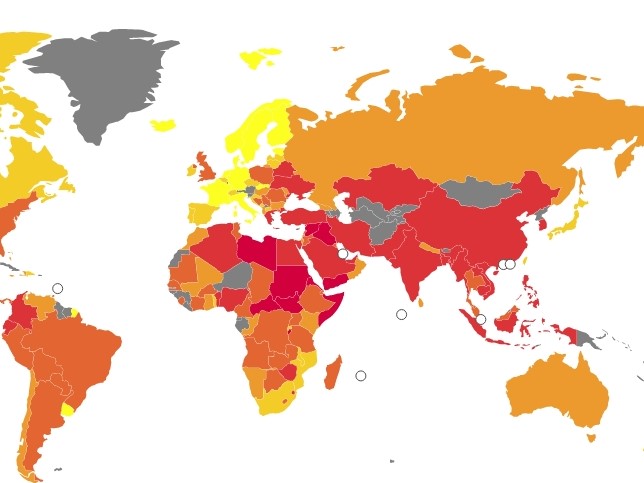

The ITUC Global Rights Index 2017 ranks 139 countries against 97 internationally recognised indicators to assess where workers’ rights are best protected in law and in practice, with an overall score placing countries in one to five rankings.

- Irregular violations of rights: 12 countries including Germany & Uruguay

- Repeated violations of rights: 21 countries including Japan and South Africa

- Regular violations of rights: 26 countries including Chile and Poland

- Systematic violations of rights: 34 countries including Paraguay and Zambia

- No guarantee of rights: 35 countries including Egypt, the Philippines and Qatar

And, 5+. No guarantee of rights due to a breakdown of the rule of law: 11 countries including Burundi, Palestine and Syria.

Source: Ethical Trading Initiative