Countries

Solidarity campaigns

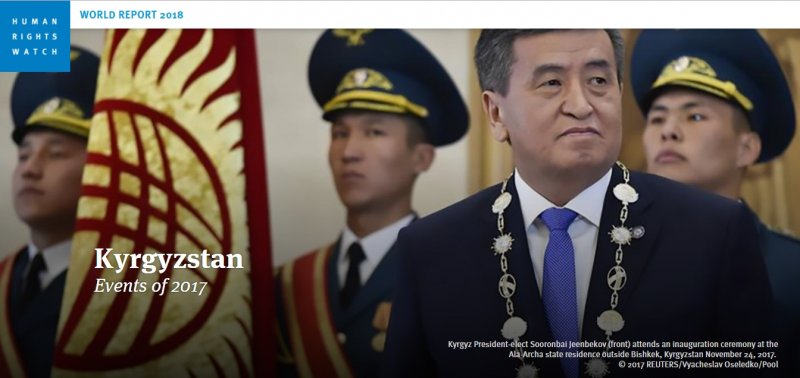

Kyrgyzstan. Events of 2017

Human rights defender Azimjon Askarov continued to serve a sentence of life imprisonment, notwithstanding his wrongful conviction and ill-treatment. Impunity for ill-treatment and torture remain the norm. The situation for media freedoms deteriorated, with the Prosecutor General’s Office bringing unjustified multimillion Som (tens of thousands of US dollars) lawsuits against critical media. Several foreign human rights workers are banned from Kyrgyzstan.Parliament in April adopted in its first reading a draft ombudsman law, aimed at bringing the institution into compliance with the Paris Principles, the international standards that frame and guide national human rights institutions. The government has yet to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Access to Justice

Authorities continue to deny justice to victims of the June 2010 inter-ethnic violence in southern Kyrgyzstan, and took no steps to review torture-tainted convictions delivered in its aftermath. Ethnic Uzbeks were disproportionately affected by the violence, which left more than 400 dead and led to numerous cases of arbitrary detention, ill-treatment and torture, and house destruction.

Azimjon Askarov has been languishing in prison in Kyrgyzstan for the last seven years...Instances of courtroom violence occurred in 2017. In April, relatives and friends of a murdered police officer hit and threatened Osh-based lawyers Muhayo Abduraupova and Aisalkyn Karabaeva, and their client, a relative of two men accused of the officer’s murder. At time of writing, no one had been held accountable.

In a March 2017 ruling, the UN Human Rights Committee determined that four ethnic Uzbeks from southern Kyrgyzstan were arbitrarily detained following interethnic violence in Osh in 2010, and ill-treated or tortured in custody. The committee concluded that Kyrgyzstan must investigate the authors’ torture allegations and provide adequate compensation. At time of writing, authorities had taken no steps to fulfill the decision.

Civil Society

The government continued to ignore its obligation to fulfill the 2016 UN Human Rights Committee decision to release rights defender Azimjon Askarov and quash his conviction, handed down after a trial marred by torture and violence. On January 24, a Bishkek court upheld Askarov’s life sentence. In September, a Bazar-Kurgon court found unlawful the authorities’ efforts to confiscate Askarov’s family home.

In May, the Supreme Court ruled against human rights defender Tolekan Ismailova, who in 2016, along with fellow rights defender Aziza Abdurasulova, had sued President Almazbek Atambaev for defamation after he publicly smeared them. On October 30, a Bishkek court found that Kyrgyzstan’s National Security Committee (GKNB) had in January disseminated false information about the human rights group Bir Duino, and ordered the GKNB to refute the information in media.

In July, following Russian human rights activist Vitaly Ponomarev’s participation in a conference on countering violent extremism, authorities banned him from Kyrgyzstan. Human Rights Watch Central Asia researcher and Bishkek office director Mihra Rittmann remained banned from Kyrgyzstan.

Freedom of Expression

In March and April, Kyrgyzstan’s prosecutor general brought five defamation lawsuits against media outlet Zanoza, its founder Narynbek Idinov, and editor Dina Maslova; Radio Azattyk, the Kyrgyz branch of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty; and human rights defender Cholpon Djakupova. The prosecutor accused them of discrediting the president’s honor and dignity and spreading false information.

Courts ordered Idinov’s and Djakupova’s bank accounts frozen and seized their property as collateral, and banned Idinov, Maslova, and Djakupova from leaving Kyrgyzstan. The prosecutor general in May withdrew the lawsuit against Radio Azattyk, but pursued lawsuits against Zanoza, Idinov, Maslova, and Djakupova. In rushed hearings in late June, Bishkek courts awarded crippling multi-million som damages, which were upheld on appeal in August. In another defamation lawsuit, a Bishkek court on October 5 awarded then-presidential candidate Jeenbekov 10 million som (US$143,000) against news portal 24.kg and Kabay Karabekov, a journalist and former member of parliament. In November, a Bishkek court banned the chief editor of Tribuna.kg, Yrysbek Omurzakov, from leaving Kyrgyzstan.

Authorities in June charged Ulugbek Babakulov, a freelance journalist and contributor to Moscow-based Ferghana News, an independent news website, with inciting ethnic hatred after a May article about the increase of nationalist and anti-Uzbek sentiments in social media. On June 10, a Bishkek court ordered Ferghana News’ website to be blocked. Babakulov, fearing for his safety, fled Kyrgyzstan in June.

On August 22, a Bishkek court ordered the closure of Sentyabr television station for disseminating “extremist material.” Authorities did not inform Sentyabr of the allegations or the court case until two hours before the hearing began. Sentyabr is tied to the opposition politician Omurbek Tekebaev, who in mid-August was imprisoned for eight years for corruption, charges which his supporters claim were politically motivated.

On September 29, a Bishkek appeals court reduced Zulpukar Sapanov’s four-year prison sentence to a two-year suspended sentence and released him. Sapanov was convicted on September 12 for inciting religious discord after his book was determined to “diminish the role of Islam as a religion and create a negative attitude toward Muslims.”

Freedom of Assembly

Authorities took steps to limit freedom of peaceful assembly. In February, a Bishkek court imposed a three-week ban on public assemblies in the Leninskii district, citing the need to ensure public order. In mid-March, five protest participants were detained during a peaceful march to support freedom of speech.

A Bishkek court in July banned public assemblies at central locations in Bishkek, including Ala-Too Square, from July 27 to October 20, citing concerns about public security before the elections. On August 9, police detained Ondurush Toktonasyrov, an activist who held a single-person protest outside the Central Election Committee building, for violating the ban. Toktonasyrov was issued a warning and released.

On November 8, a Bishkek court, citing the then-upcoming presidential inauguration on November 24, banned public gatherings in several locations in central Bishkek until December 1.

Torture and Ill-Treatment

Impunity for torture remains the norm, and investigations into ill-treatment and torture allegations remain rare, delayed, and ineffective. Kyrgyzstan’s Coalition Against Torture, a group of 16 nongovernmental organizations working on torture prevention, reported in February that the prosecutor’s office had registered 435 complaints of ill-treatment in 2016, but declined to open investigations into 400 cases. Sardar Bagishbekov, a representative of the coalition, noted that, on average, the prosecutor’s office declines to investigate torture allegations in over 90 percent of cases.

Violence against Women

In April, Kyrgyzstan adopted a new Law on the Prevention and Protection against Family Violence, which requires police to register any domestic abuse complaint, and recognizes physical and psychological abuse, and “economic violence,” which includes restricting access to and use of financial resources or other assets. The law mandates police and judicial response to domestic violence, and ensures victims’ access to shelter, psychosocial support, and legal aid. Some provisions of the law lack specificity and survivor protections.

Despite positive legislative changes, domestic violence remains widespread. Pressure to keep families together, stigma, economic dependence, and fear of reprisals by abusers, or limited services and police hostility and inaction hinder survivors from seeking assistance or accessing protection or justice.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people continued to experience ill-treatment, extortion, and discrimination by both state and non-state actors. There is widespread impunity for these abuses. Consideration of an anti-LGBT bill, which would ban “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations,” remained stalled in parliament.

Several days before a peaceful public gathering planned for September 23, five law enforcement officers arrived unannounced at Labrys, a Bishkek-based LGBT rights group, threatening members not to hold the gathering. Labrys cancelled the event.

Terrorism and Counterterrorism

The government stepped up counterterrorism measures following deadly attacks abroad that investigators linked to armed extremists of Central Asian origin, arresting scores of people for storage of vaguely defined “extremist” materials, an offense which carries a mandatory prison sentence of three to five years. As of August, 191 people had been imprisoned for terrorism or extremism-related offenses. Many were ethnic Uzbeks who alleged they had been arrested based on false testimony or evidence planted by the police, and that they were tortured and otherwise abused in police custody.

An overly broad constitutional amendment approved in December 2016 aims to revoke citizenship of Kyrgyz nationals who join international terrorist organizations. The measure awaited enabling legislation.

Key International Actors

In January, the European Union timidly reacted to a Bishkek court’s decision to uphold Askarov’s life sentence. EU leaders failed to publicly call for Askarov’s release during meetings with President Atambaev in February and in November, nor has the EU publicly made any other reference to Askarov’s case at time of writing.

Brussels hosted the 8th annual EU-Kyrgyzstan human rights dialogue in June. The EU commended Kyrgyzstan for its new domestic violence legislation, and called on the government to ensure media freedoms, enable transparent presidential elections, and protect the rights of ethnic minorities. Concrete outcomes were not known at time of writing.

In a meeting with President Atambaev in June, UN Secretary-General António Guterres failed to express concern about worrying media freedom developments, and instead praised the government for upholding the rule of law, protecting human rights, and serving as a “pioneer of democracy in Central Asia.” Guterres did not meet activists in Bishkek.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) announced in April that as of May 1, it would downgrade its presence in Kyrgyzstan to an “OSCE Programme Office.”

Source: Human Rights Watch