Countries

Solidarity campaigns

Uzbekistan: 2 Activists Freed, Others Arrested Guarantee Freedom to Express Critical Views

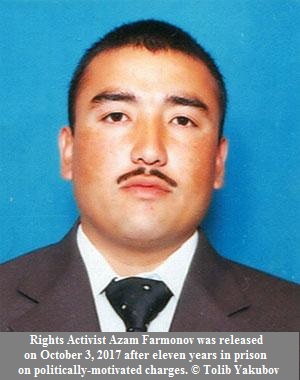

Azam Farmonov, a human rights defender, tortured and unjustly jailed since 2006, was freed on October 3, and Solijon Abdurakhmanov, an independent journalist unlawfully in prison since 2008, was freed on October 4. Prison authorities had also improperly charged Farmonov with “violations of prison rules,” extending his sentence by five years. Both were granted early release on the orders of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the families said.

“The release of Azam Farmonov and Solijon Abdurakhmanov after long years of abuse was positive news, but there should be no revolving door for political arrests,” said Steve Swerdlow, Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “President Mirziyoyev should see to it that all political prisoners are released and that all of Uzbekistan’s citizens are guaranteed the fundamental right to peacefully express critical opinions.”

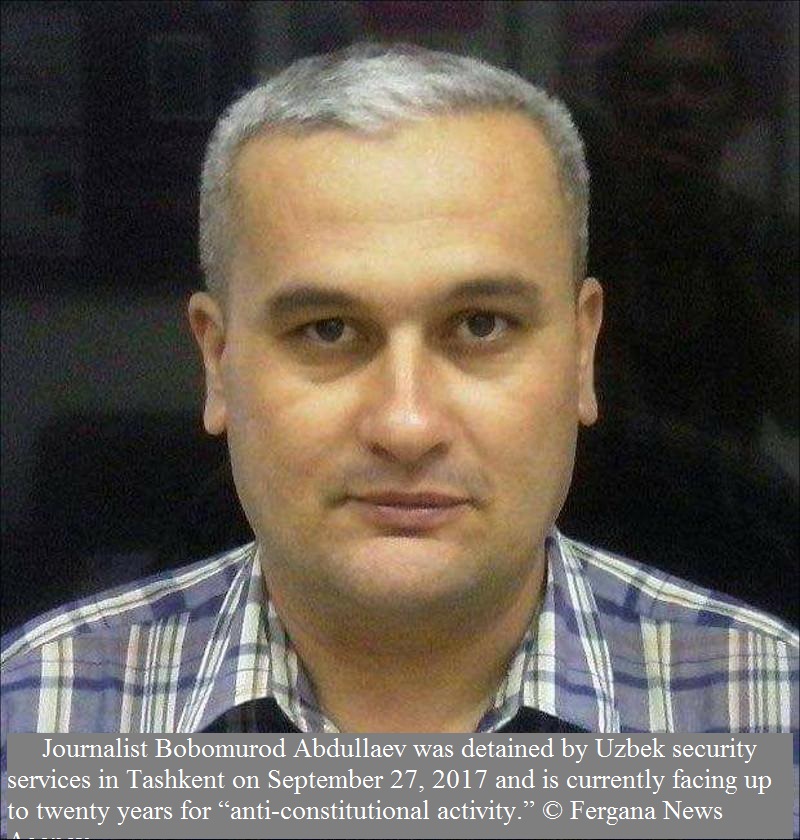

On September 27, Uzbek security services detained Bobomurod Abdullaev, an independent journalist, in Tashkent, on what appears to be a politically motivated charge. He was charged with “attempts to overthrow the constitutional regime” under Article 159 of Uzbekistan’s Criminal Code, and faces up to 20 years in prison. He remains in custody.

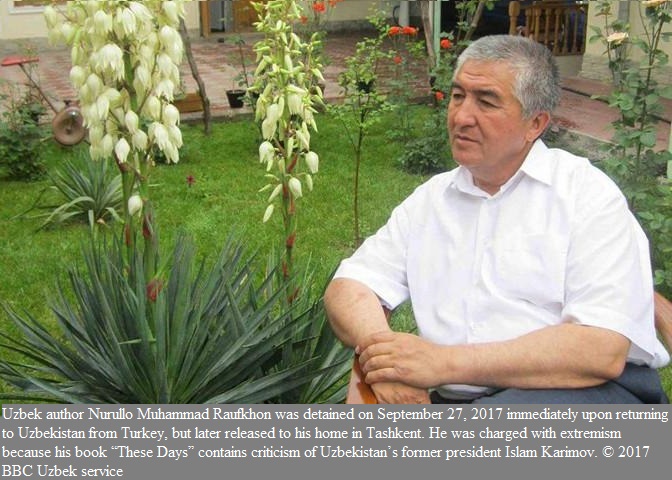

Police also detained Nurullo Muhummad Raufkhon, an Uzbek author, at Tashkent airport on September 27, after he had arrived from Turkey. He was charged with extremism for a work of literature that criticizes Uzbekistan’s former authoritarian president Islam Karimov. He was released on October 1, but still faces charges.

Police also detained Nurullo Muhummad Raufkhon, an Uzbek author, at Tashkent airport on September 27, after he had arrived from Turkey. He was charged with extremism for a work of literature that criticizes Uzbekistan’s former authoritarian president Islam Karimov. He was released on October 1, but still faces charges.

Uzbek authorities should drop politically motivated charges that stem from the exercise of basic human rights and release all those imprisoned as a result of such charges, Human Rights Watch said. Mirziyoyev should also send an unambiguous message to all law enforcement that no one in Uzbekistan will be punished for the peaceful exercise of free speech.

Farmonov and Abdurakhmanov are the sixth and seventh political prisoners released since Mirziyoyev became acting president in September 2016, following Karimov’s death in August 2016. Since formally assuming office in December, Mirziyoyev has taken some steps to improve the country’s abysmal human rights record, such as relaxing some restrictions on free expression, removing citizens from the security services’ notorious “black list,” and increasing the accountability of government institutions. But Uzbekistan’s government remains authoritarian and has yet to transform these modest steps into institutional change and sustainable improvements.

Mirziyoyev should direct the relevant authorities to effectively investigate allegations that Farmonov suffered torture in prison, and that both he and Abdurakhmanov were convicted following proceedings that violated basic fair trial standards, Human Rights Watch said. The Uzbek government should also immediately and unconditionally release all other peaceful activists, including Abdullaev, and drop the charges against Raufkhon.

Mirziyoyev should direct the relevant authorities to effectively investigate allegations that Farmonov suffered torture in prison, and that both he and Abdurakhmanov were convicted following proceedings that violated basic fair trial standards, Human Rights Watch said. The Uzbek government should also immediately and unconditionally release all other peaceful activists, including Abdullaev, and drop the charges against Raufkhon.

“The Uzbek government should do everything it can to ensure that the prison officials and police who violated Farmonov and Abdurakhmanov’s rights are held accountable,” Swerdlow said. “But the continued arrests of critical journalists and writers casts a pall over what would otherwise be a sign of hope.”

Azam Farmonov

Farmonov, 38, a father of two children, was chairman of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan in Gulistan, Syrdaryo region. He defended the rights of farmers and people with disabilities, including representing them in court as a lay defender. He was arrested on April 29, 2006, alongside another rights activist, Alisher Karamatov, on fabricated charges of extortion, and sentenced to nine years after being tortured to confess and a trial marred by serious due process violations.

Farmonov’s sentence was to expire on April 29, 2015. But on April 6, authorities transferred him from the Jaslyk prison colony in Nukus, more than 800 kilometers from Tashkent, to a punishment cell in the city of Nukus for unspecified “violations of prison rules” – a practice Uzbek authorities have typically used before extending the sentences of those imprisoned on politically motivated charges.

On May 21, 2015, Farmonov's wife, Ozoda Yakubova – the daughter of prominent human rights defender Tolib Yakubov, now in France – received a phone call from a former detainee in the Nukus pretrial detention center informing her that a regional court had extended Farmonov's sentence by five years for allegedly violating prison rules, and that he had been transferred back to Jaslyk prison. Yakubova was not notified of the trial dates for the extension and neither she nor any independent observers were able to attend the trial.

Solijon Abdurakhmanov, 67, father of six children, was an outspoken journalist and rights activist with the Committee for the Protection of Individual Rights. Based in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic in northwest Uzbekistan, he reported for the independent news portal Uznews.net, Ozodlik (the Uzbek service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty), Amerika Ovozi (Voice of America), and the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. He covered sensitive issues such as social and economic justice, environmental problems of the Aral Sea, corruption, and the legal status of Karakalpakstan within Uzbekistan.

Security service officers arrested Abdurakhmanov on June 7, 2008 on fabricated drug possession charges. During pretrial detention, authorities questioned Abdurakhmanov about his journalistic work and denied him access to his legal team. On October 10, 2008, a court sentenced him to 10 years in prison following a trial that did not meet fair trial standards. After his conviction, both of Abdurakhmanov’s defense lawyers – his brother, Bahrom Abdurakhmanov, and Rustam Tyuleganov – were disbarred by the government-controlled bar association following a re-attestation process that violated international norms on the independence of lawyers, and appeared to be in retaliation for their work.

Abdurakhmanov served his sentence in Karshi, more than 700 kilometers from his home. As recently as September 7, 2017 Abdurakhmanov’s wife told Human Rights Watch that prison authorities had charged Abdurakhmanov with numerous “violations of prison rules” that render him ineligible for amnesty or early release. The alleged violations included “not marching correctly” and “not sweeping up his cell”. She also reported that he had a severely aggravated stomach ulcer and suffered other serious medical complications in prison. Abdurakhmanov’s family, rights groups, and independent media reported that prison authorities had prevented International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) representatives from meeting him in prison. In fall 2012, prison officials attempted to pass off another prisoner as Abdurakhmanov when ICRC representatives visited the facility, a ruse quickly recognized by observers.

Source: Human Rights Watch