Countries

Solidarity campaigns

Uzbekistan: WE NOW HAVE RIGHTS, BUT HOW TO IMPLEMENT THEM?

On October 15, the president Shavkat Mirziyoyev signed a new law “On the rights of persons with disabilities”. What measures must be taken so that it does not repeat the fate of the previous law – “On social protection of disabled people” – and really protects their rights and interests? Together with Oybek Isakov, Chairperson of the Association of Disabled People of Uzbekistan (an umbrella NGO uniting 28 public organisations of/for disabled people) we published an article in Russian at Gazeta.uz.

The law “On the Rights of Persons with Disabilities” can rightfully be considered an achievement of national legislation, because for the first time disability was defined not as a problem of social protection or healthcare, but primarily as a human rights issue. One of the main legal innovations is the concept of “disability-based discrimination,” which previously did not exist in the national legislation of Uzbekistan.

The new law was developed with the direct and active participation of disabled people themselves under the auspices of the Association of Disabled People of Uzbekistan. The draft developed by the Association was used as the basis of the law, and about 60% of proposals of disabled people were included in the final version of the law. However, some of the articles previously proposed by the Association were not included in the law. Furthermore, the most important question remains open: will the new law work in practice?

Still medical definition of disability

Although the law speaks of the rights of persons with disabilities, the definition of disability is still not based on a human rights-based approach. In the law, disability is equated to persistent physical, mental, sensory or mental impairments, and persons with disabilities are defined as those in need of “social assistance and protection, creating conditions for full and effective participation on an equal basis with others in political, economic, the social life of society and state”.

However, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) recognises that “disability is an evolving concept and that disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

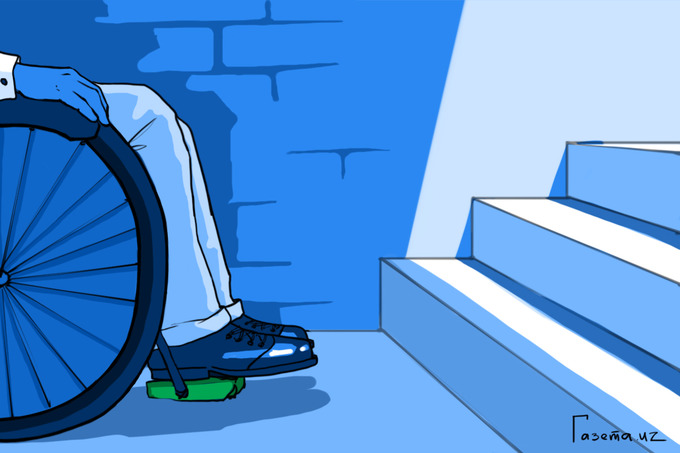

Source: Illustration by the authors.

A purely medical definition of disability focuses the attention of “medical and social expertise” only on identifying the “degree of loss of health” of a person as the basis for determining the “degree of disability.”

This approach to assessing disability does not fit the biopsychosocial model according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). In other words, the limitation of human activity occurs not only because of the individual health conditions but also due to environmental factors.

How to realise the right to protection from disability-based discrimination?

Article 6 of the new law reflects the principle of non-discrimination based on disability:

“Any isolation, exclusion, deprivation, restriction or preference in relation to persons with disabilities, as well as refusal to create conditions for persons with disabilities to access facilities and services is prohibited.”

In other words, if, for example, there is no accessible physical environment in a public institution or transport, then based on the law people with disabilities can sue an organisation that does not provide the necessary conditions for free movement. But for them to be able to sue that organisation, access to justice must be provided in the first instance.

CRPD has article 13 on access to justice. Unfortunately, a similar article, proposed by the Association of Disabled People, was not included in the final law. However, certain provisions of this article were included. For example, article 28 of the new law states that deaf and hard of hearing persons must be provided with sign language interpreters during investigations and court hearings. Article 29 establishes the right to use a facsimile signature (specially made stamp), which is mainly used by blind and visually impaired people.

However, to realize the legitimate rights of people with disabilities, it is necessary to develop a specific mechanism for ensuring access to justice. Catalina Devandas Aguilar, Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, recently stated that buildings of courts and law enforcement institutions remain inaccessible in various countries. In this regard, the UN has developed “International principles and guidelines on access to justice for persons with disabilities.”

Diego García-Sayán, Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, following his visit to Uzbekistan last year, recommended: “to remove the architectural and linguistic barriers that now impede or restrict the right of persons with disabilities to access justice on an equal basis with others.” In his report, he expressed concern about the partial or complete inaccessibility of court buildings, especially outside the main cities, the lack of sign language interpreters and the lack of court documents in accessible formats for persons with sensory, intellectual or psychosocial impairments.

Applying to court may entail additional financial costs. But can people with disabilities bear these costs? As a result, those who have experienced disability-based discrimination on themselves can turn a blind eye to it, so as not to waste their limited time, money and energy fighting windmills. Moreover, what if even the courts do not provide an accessible environment and reasonable accommodations for them?

Moreover, how to assess moral damage from discrimination based on disability, and who will compensate it? It is necessary to think carefully about all these points, given the possible low level of legal knowledge and awareness of people with disabilities themselves.

Accessible environment – mission impossible?

The previous law “On social protection of disabled people” already established administrative liability “for failure to fulfil obligations to ensure unimpeded access of disabled people to social infrastructure facilities, use of transport, transport communications, means of communication and information.”

However, according to the Public Council under the Tashkent khokimiyat (city administration), “85% of buildings and social infrastructure facilities are not adapted for use by persons with disabilities.” Transport infrastructure remains inaccessible in the capital, not to mention the regions of the country.

Will the new law be able to change this dire state of affairs? No matter how many laws prescribe the need to create an accessible environment, the situation will not change without the introduction of specific mechanisms for ensuring an accessible environment. Unfortunately, the law does not include the concept of “universal design” enshrined in the CRPD as:

“…the design of products, environments, programmes and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. “Universal design” shall not exclude assistive devices for particular groups of persons with disabilities where this is needed.”

Article 23 of the new law obliges to carry out the commissioning of construction and reconstructed objects of social, domestic and cultural purposes with the inclusion of representatives of public organisations of disabled people in the state acceptance commission.

In this regard, it is necessary to strengthen the capacity and actively involve NGOs of people with disabilities not only in the acceptance but also in the design of social infrastructure facilities based on the laws “On public control” and “On social partnership”. All categories of disabled people must participate in these processes, where possible, because they all have different accessibility needs.

Sign language status and subtitles

Under the new law, the state guarantees the receipt of information in accessible formats. State-owned TV channels should provide news coverage with sign language interpretation or subtitles (captioning).

It would be good if, before the law came into force on January 16, 2021, the National Television and Radio Company of Uzbekistan began to develop technology for automatic recognition of Uzbek speech for the introduction of subtitles on national TV channels. Given the limited number of sign language interpreters, subtitles could provide full access to information for deaf and hard of hearing people and increase their literacy. At the same time, the broadcast would not be limited to news programs only.

Unfortunately, in the new law, sign language remained only a “means of interpersonal communication”, as it was defined in the old law “On social protection of disabled people.” The main assistance of the state to the development and use of the sign language would be to give it the status of the state language, in which one can receive an education. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a draft resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers “On the status of sign language”, which would determine the mechanism for the introduction and development of sign language in Uzbekistan.

A vague mechanism for realising the right to inclusive education

Article 38 of the law stipulates that “the state guarantees the development of inclusive education for persons with disabilities” throughout their lives, from preschool to postgraduate education. However, the mechanism for realising the right to receive inclusive education remains unclear. Therefore, the adoption of a separate normative act “On inclusive education” is required.

The new version of the Law “On Education” introduced Article 20, which defines inclusive education. Nevertheless, the law states that “the procedure for organising inclusive education is determined by the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan.” According to the available information, such a procedure has not yet been developed.

The main problem is that the opinions of “specialized doctors” can play a decisive role in determining the “educability” or “learning disability” of children and adults with disabilities at mainstream educational institutions. Doctors’ recommendations are often of mandatory nature rather than advisory, which will hinder the realisation of the right to inclusive education.

Will the employment quotas work?

As in the previous law, the new law retained the powers of local government bodies to establish the minimum number of workplaces for the employment of persons with disabilities in the amount of at least 3% of the total number of employees.

The previous Law “On Social Protection of Disabled People” already obliged local government authorities at enterprises, institutions and organisations with more than 20 employees to provide employment quota in the amount of at least 3% of the number of employees.

Have the employment quotas worked in favour of the disabled people? I think the answer is obvious. According to the UN situational analysis of children and adults with disabilities, only about 7% of registered persons with disabilities are officially employed in Uzbekistan. At the same time, according to other sources, only 2% of people with disabilities are employed. The reason for the ineffectiveness of employment quotas may lie in unsatisfactory monitoring of the implementation of legislation.

The Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations, which has the mandate to collect fines for non-compliance with the 3% employment quota, does not monitor compliance with the law properly. If the “stick approach” is not giving the expected results, maybe it is worth trying the “carrot approach” and rather motivate government agencies and the private sector to employ people with disabilities?

As an alternative solution to the problem of employment, the following can be offered: local government bodies and enterprises can assist in the provision of non-residential premises, land plots on favourable terms, in the acquisition of raw materials and product marketing of specialized enterprises under public associations of disabled people, as well as persons with disabilities who carry out individual entrepreneurial activities. However, unfortunately, this proposal of the Association was not included in the law.

How will a decent living standard and social protection be ensured?

The law also did not include articles on providing persons with disabilities and their families with an adequate standard of living, taking into account their basic needs for food, clothing, housing, free medical care, and the necessary social services to maintain their health and well-being.

The key point here is the amount of pensions and disability benefits, which cannot be set below the minimum subsistence level. This is enshrined in the Constitution of Uzbekistan.

However, the official amount of the minimum subsistence level and the consumer basket have not yet been approved. Based on the level of inflation, it is necessary to annually make adequate indexation of pensions and benefits paid to children and adults with disabilities, as well as their guardians.

Data collection is under question again

Article 31 of the CRPD provides for the collection of appropriate statistical information and research data on disability. However, a similar article on data collection proposed by the Association of Disabled People was also not included in the final version of the law.

Legislators argued that on March 22, 2018, a separate resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers “On improving the system of statistical registration of persons with disabilities” was adopted. It is unclear exactly how this regulation is implemented in practice. Available data on disability remain scarce and do not fully reflect the livelihoods of persons with disabilities.

Open data on disability is essential to monitor our progress towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Disability issues are included in five goals, including poverty eradication, good health and well-being, gender equality, reducing of inequalities, and development of sustainable cities and human settlements.

For effective social protection and monitoring of the socio-economic situation of people with disabilities, the state should organise and conduct the regular collection of comprehensive statistical data covering all spheres of life of people with disabilities. Regular analysis of such data makes it possible to identify pressing problems, assess the situation of various groups of persons with disabilities, and keep a separate record of the availability of accessibility environment for them.

Comprehensive statistics on the livelihoods of disabled people should include but are not limited to: gender, age, place of residence, disability category, education, employment, housing needs and improvement of housing conditions, transportation and rehabilitation means, sports, involvement in social, political and cultural life, as well as other spheres of life.

We need mechanisms to realise our rights

Analysis of the new law “On the Rights of Persons with Disabilities” showed that it does not fully comply with the provisions of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The definition of disability is still medical in nature, contrary to international standards based on a human rights-based approach to the definition of disability.

The new law excludes such important concepts as “universal design”, statistics and data collection on disability; sign language is not equated in status with a full-fledged language on a par with the state language. Obviously, after the ratification of the convention, the question of bringing this law in accordance with the provisions of the convention will arise.

For the law to work, it is imperative to raise the level of legal literacy and awareness of persons with disabilities themselves and their guardians. This can be achieved by ensuring the availability of legal services and practical legal assistance through the network of consulting bureaus of the NGO Madad, established by the Ministry of Justice.

It is also necessary to strengthen the organisational capacity and provide funding for self-initiative NGOs of disabled people to implement projects aimed at raising legal awareness of disabled people, especially in the rural areas of the country.

Most importantly, we need to work out specific mechanisms for realising the rights of persons with disabilities to protection against disability-based discrimination; coordination of construction projects with NGOs of people with disabilities for compliance with the principles of environmental accessibility and universal design; choice of the form of education and employment, as well as a decent standard of living.

Source: dilmurad.me

Posted 24 Oct. at 10:54h in Access to Justice, Disability Rights, Inclusive Education, Inclusive Employment, Social protection by Dilmurad Yusupov 0 Comments

Illustration: Eldos Fazylbekov / Gazeta.uz.